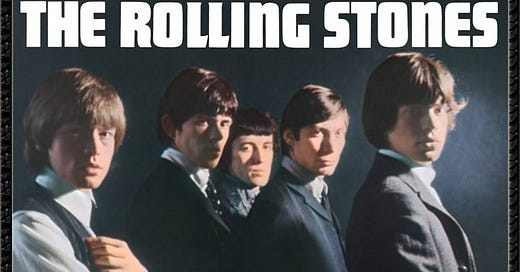

The Rolling Stones - England's Newest Hit Makers (Decca, 1964)

In which my longstanding skepticism of the Stones is validated by reading Wikipedia and lining up some of the dates.

“The ROLLING STONES are more than just a group-they are a way of life. A way of life that has captured the imagination of England’s teenagers, and made them one of the most sought after groups in Beatdom. For the Stones have their fingers on the pulse of the basic premise of “pop” music success-that its public buys sound, and the sound is what they give you with this their first album; a raw, exciting basic approach to Rhythm and Blues which, blended with their five own explosive characters, has given them three smash hits and an E.P. that stayed in the single charts for fifteen weeks. In the eight months since the Stones embarked on their pop career, they have not only chalked up major chart successes, but smashed attendance records on tours the length and breadth of the country. They have emerged as five well rounded intelligent talents, who will journey successfully far beyond the realms of pop music. And in this album are twelve good reasons why.”

- from the back of the dust jacket of this record, by Andrew Loog Oldham, who you’d think would be a music critic or arts and culture reporter, but was actually the Rolling Stones’ manager and producer from 1963-1967

I’ve long held a skepticism that the Rolling Stones were as culturally significant as I was repeatedly told they were when I was a teenager in the early 90s. To be fair, I was leaning hard into the noncommittal cynicism of grunge music at that time, and some trace elements of that cynicism linger. Nonetheless, they seemed always positioned in relation to someone else - The Beatles, the mainstream, black people making the R&B music they were covering - and not something from which that culture originated. I’m sure this isn’t fair, but to me, it seemed like the Rolling Stones were benefitting from the distorting effects of long-term nostalgia, and so should have similarly grandiose expectations foisted upon them. You can say the same about Dylan, or any number of others.

Even the conspicuous placement of “Beatdom” in the above, fawning paragraph is a conscious attempt to capitalize on the fading relevance of the Beat movement, as opposed to anticipating the flower power counter-culture of the coming summer of love. In 1964, Kerouac had not written anything in years, and yet was being ripped off in the mainstream:

The television series Route 66 (1960–1964), featuring two untethered young men "on the road" in a Corvette seeking adventure and fueling their travels by apparently plentiful temporary jobs in the various U.S. locales framing the anthology-styled stories, gave the impression of being a commercially sanitized misappropriation of Kerouac's story model for On the Road. Even the leads, Buz and Todd, bore a resemblance to the dark, athletic Kerouac and the blonde Cassady/Moriarty, respectively. Kerouac felt he'd been conspicuously ripped off by Route 66 creator Stirling Silliphant and sought to sue him, CBS, the Screen Gems TV production company, and sponsor Chevrolet, but was somehow counseled against proceeding with what looked like a very potent cause of action.

Invoking The Beats, who appropriated black jazz, on a debut album almost completely made up of R&B covers, at the same times as The Beatles were putting out albums full of originals like A Hard Day’s Night and Beatles for Sale, just never say quite right to me, or as worthy of praise.

I picked up several used Stones albums on vinyl the other day, thinking that perhaps it was time for a re-appraisal. I could use a Stones renaissance, as I experienced with the Beatles when I was in high school. My mother, from Liverpool, played us the Beatles growing up, so much so that I discounted them as my parents’ music. They were the mop-topped boy band that teenaged girls screamed over. It wasn’t until I listed to Revolver that you could find me telling people that The Beatles were really good. (To which I usually received a sarcastic “Great find, man! Deep cut!”)

On the recently released Beatles ‘64 documentary (which I thought was terrible, but that’s the subject of another post), archival footage of a Lennon interview included something to the effect that he didn’t believe culture originated with The Beatles, but that culture was a big ship on which we were all passengers, and The Beatles were simply up in the crow’s nest saying “land ho!” I thought that was an admirably humble thing for Lennon to say. Also notable to me, however, was his inclusion of the Stones in that crow’s nest - “maybe the Stones are up there, too.” To the extent that I enjoy that elegant metaphor, I get it. The Beatles and The Stones, like The Beats, were simply saying “there is something happening in the culture which the squares are not paying attention to.”

England's Newest Hit Makers is the American release of the Stones’ first album, which was released in the UK as a self-titled debut. That helps to explain, somewhat, the hysterical announcement on the back of the dust jacket, declaring to curious American youths that to listen to the Stones was not to listen to music by a band, but to consider joining a movement.

To some extend, this makes sense. Just two years later, Timothy Leary would utter his famous “turn on, tune in, drop out,” in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park to a gathering of 30,000 hippies. The option presented is one by which the listener rejects the status quo, celebrates the underrepresented, and loses themselves in the expression of the moment:

Like every great religion, we seek to find the divinity within and to express this revelation in a life of glorification and the worship of God. These ancient goals we define in the metaphor of the present—turn on, tune in, drop out.

I can only imagine the experience of freedom that came from, for perhaps the first time, letting yourself feel rhythm and dance. Like so many kids born in the 80s, I grew up exposed to the glorification of these principles as if they were more than simply the appropriation of worship tropes to trickle some bit of the influence in another direction (but then there’s that cynicism again). I think it’s telling that the Stones’ manager also said, at around this time:

“Cast deep in your pockets for loot to buy this disc of groovies and fancy words. If you don't have bread, see that blind man, knock him on the head, steal his wallet and low and behold you have the loot, if you put in the boot, good, another one sold!”

— Andrew Loog Oldham

It’s no great surprise, I suppose, that every era has its hucksters and grifters, alongside true visionaries and explorers. Differentiating between the two is how critics used to get their jobs, so who am I to complain? It’s also of course possible that the Stones are Right and True and Plugged In to the culture, and they simply had a sleazy manager who liked to be quoted in the media.

That lengthy preamble aside, I was excited to listen to the debut album of a band that genuinely animated a generation, alongside others who I might consider more authentically experimental or relevant. Do I think The Strokes were doing anything interesting? Not really. Is Is This It? an aesthetic masterpiece? I think so. If England's Newest Hit Makers was little more than the Is This It? of its day, you can certainly do far worse than that when spending $15.

Anyway, here they are on the Ed Sullivan Show making music that, like so much rock n’ roll at the time, is basically about rock n’ roll and how it’s great. It’s funny the degree to which this stuff, with all of its “they never stop rocking” and “what a crazy sound” sounds to me like children’s music today.

“Time is On My Side” (starting at about 3:15), which is not on England's Newest Hit Makers, definitely feels more like the Stones making their mark on an otherwise standard R&B format, this song first being covered by Irma Thomas. At this point, perhaps I’m too invested in taking the piss out of the Stones to admit that I enjoy this music, but I do think it’s worth noting the degree to which actual R&B bands kick the living hell out of the Stones’ rougher garage band style.

It’s difficult to hear in this tinny approximation of R&B music the bona fide cultural phenomenon that catapulted the album to number one for 15 straight weeks, but it has a kind of effortless quality to it that makes possible putting it on in the background of a noisy bar, almost ambient for shared spaces where people seek out one another’s energy. I never felt like I was plugged in to 64’s zeitgeist the way I still do when I hear The Beatles, but I can see how the Stones could become a kind of minor planet in the galactic explosion of 60s music.