When I was 21 years old, I played in a band called in my hometown of Ottawa. The arc of the band adhered roughly to that of most Ottawa-based rock bands: in your late teens or early 20s you identify 2-3 other people, usually men, who share you tastes in music. You write some songs, look at one another, say, “now what?” and start to book shows. You pressure you friends to attend, roughly the equivalent of asking the people who support you to pay out-of-pocket to watch you enjoy your hobby. If you’re lucky, you get to open for some out-of-town bands you like. Maybe you cosplay as a working band and sell some merch, or make a recording. And finally, after a few years of this, when faced with the question of whether you’re going to move to Toronto and make an honest-to-god go of it, you break up.

I count myself lucky to have been in a band that made it as far as that latter step. In our time we got to open for The Dismemberment Plan, The Constantines, and Ted Leo and the Pharmacists, three bands who form a kind of triumvirate of influences for me. (And probably any number of other interchangeable white dudes whose story resembles my own.) And of those three, Ted Leo has come to inhabit an ideal of an artist that is uncompromising without resorting to provocation, who wears the cost of that dedication proudly. Who appeared in my hometown and made clear the difference between a band that aspired to the work and an artist whose life is the work.

There’s something that feels special to me about the way I came to be fixed in Ted Leo’s orbit. We were asked to open the show and, at the time, none of us knew who “Ted Leo and the Pharmacists” were. It wasn’t a name that piqued my interest, knowing that some musicians, when choosing a band name, default to the humorous or inane. We played Bumpers in Ottawa, a small upstairs bar and downstairs pool hall that accommodated perhaps 40-50 if packed tightly. It was a weeknight, in the winter, in Ottawa, and there were very few people there. We played for our friends. Then Ted Leo took the stage.

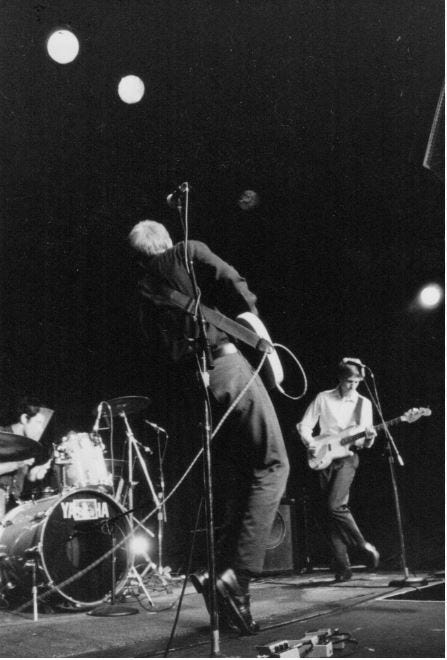

He opened with “Timorous Me,” a song from the recently released Tyranny of Distance, and it’s difficult for me to describe the effect it had on me to see Ted take the stage solo and to play with full-throated enthusiasm and distortion the opening 90 seconds of that song before the band took their places behind him and came in in unison. This moment was close to epiphany as I get. When the song ended, I whooped, and Ted said, “well, don’t stand back there, then, get up here,” and I moved to the front where, alongside what must have been five or six others, I proceeded to be destroyed by the energy, the melody, the unabashed refusal to acknowledge that they were playing a crummy weeknight show in Ottawa.

That made an immediate impression on me, the sense that one of the marks of a real artist must be the ability to play with the same sincerity and passion whether performing for one person or one thousand people, to find meaning in the performance rather than the accoutrement of approval that is large crowds and television interviews.

The next day, when I showed up for my shift at the strip mall record store where I worked, I asked my manager if we could order in a half-dozen copies of Tyranny of Distance so that I could proudly display them under my name on the staff recommendations wall. For the next six months those CDs sat there, unpurchased, and I wondered if there was any justice in the world. How could a life-changing record just sit there, undiscovered, by so many?

Leo came back to Ottawa about a year later and the show was much fuller. By his third show, I couldn’t get in. When I saw him perform in Vancouver several years later, I chatted with him after the show and mentioned I was from Ottawa. “Oh, yeah - Bumpers!” he replied.

My reverence for Ted Leo only grew. A cursory glance at Ted Leo’s website during those years revealed a workmanlike approach to touring unmatched in my experience. He would play 200+ shows per year and you could be sure each was in a small city’s equivalent of Bumpers for crowds that rarely reached three dozen. He had an influence in this incremental way, chipping away at the vast indifference of listeners with oceans of music to choose from. I like to think he was converting people like me at each show.

Ted Leo would peak in the years soon to follow, 2003’s Hearts of Oak riding that same early 00s wave of indie rock celebrated by Pitchfork, earning ‘Best New Music’ and an 8.3. To see him play the Pitchfork Music Festival in 2006, it felt like some order had been restored; here was a hard working, talented musician being recognized for being hard working and talented.

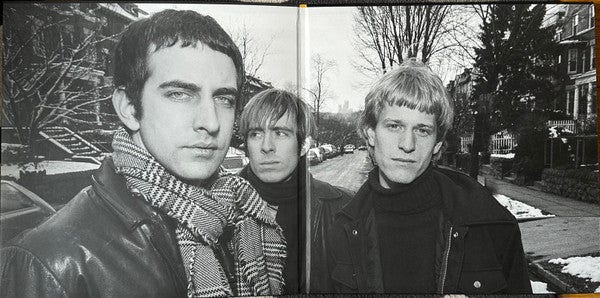

So, it was with great enthusiasm that I learned that the excellent Numero Group (about whom I wrote more here) has re-released Set You Free, from Leo’s 90’s mod-revival band Chisel. It’s in Chisel that you find the blueprint for Leo’s brand of engaged, invested, angry, but hopeful, punk.

What I hoped not to find, but did, in the liner notes of this excellent re-issue was evidence of tragedy. Ted Leo has found himself on the verge of breakthroughs again and again, but has never quite gotten there. If the early 00s it was because he was slotted alongside Broken Social Scene and Interpol in a kind of post-alternative indie music renaissance. In the late 90s it was because record labels were still looking for an alternative act to sign. I assumed that Chisel remained a critical darling but relative unknown because of the injustices perpetuated against artists by soulless tastemakers of commercial record sales. Alas, I learned that Chisel were in fact courted by labels, but turned them down.

It’s easy to admire this kind of purity test in the moment. Then, like many, I read Stereogum’s lengthy, authoritative 2017 interview with Ted Leo on the occasion of the release of his album The Hanged Man. It turns out that the life of the uncompromising indie punk musician has kind of chewed up Leo and spit him out, despite him being a universally admired and unimpeachably consistent artist. Following the success of Hearts of Oak, Leo struggled to find success, hitting true financial hardship after a disastrous European tour for 2010’s The Brutalist Bricks. His partner encountered complex health needs requiring borderline medical bankruptcy. He was coming to terms with the sexual abuse he’d suffered as a child. The bottom fell out of the business model for touring musicians and recording artists everywhere. The Hanged Man was released with help from fans via Kickstarter and, despite positive reviews, promptly disappeared.

It’s easy to see why a person would want to root for Ted Leo’s success. He’s an undeniable talent. He’s one of the hardest working musicians in a field where you have to work unbelievably hard to scratch out the meagerest of livings. He’s genuine. And he’s suffered without giving in to tragedy, again and again. You want to be able to say to the younger Leo, whose work with Chisel was remarkably consistent and good, to go a little easier on himself, to allow himself success, because the climb would only get steeper.

This summer, Ted Leo and the Pharmacists embarked on a short reunion tour to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Shake the Sheets, which remains one of my all-time favorite records. At 54, Ted Leo is at an uncertain moment in the career of a touring punk musician. His body of work is remarkably deep, and Set You Free is an essential starting point for the an appreciation of Ted Leo the songwriter. But, ultimately I continue to struggle with what Ted Leo’s relative lack of breakthrough success means because there’s relevance there to what the meaning was of any of those years that so many of my friends and I spent talking into our bubbles about our ethics and performing music for our friends. Sometimes, all there is to do is root with every fiber of your being for good people who refuse to give in.